Is it a bird? Is it a plane?

No! It’s superannuation and I’ll be in Naarm soon unpacking why it’s failing young people (and how we can fix the system together).

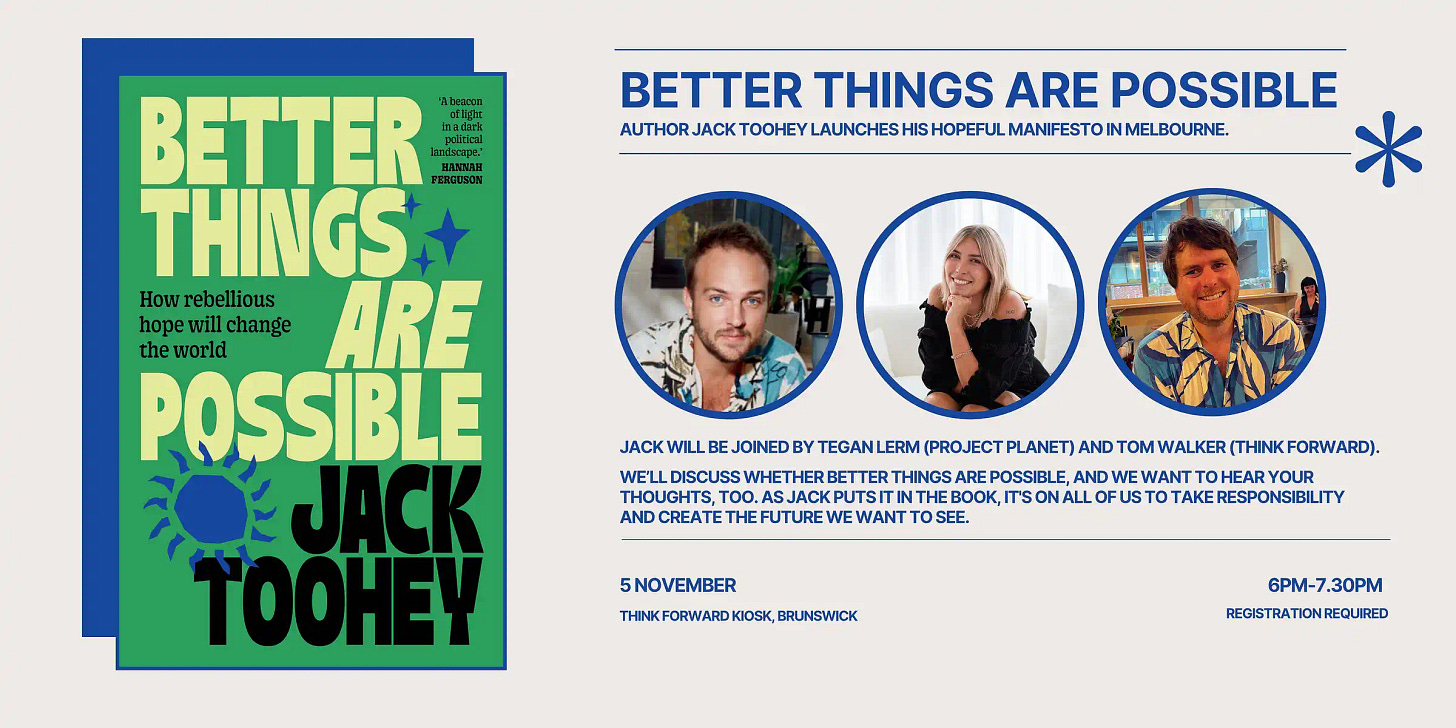

In a couple of weeks, I’ll be headed down to Naarm/Melbourne for a (FREE!) book event with my mates at Think Forward and Project Planet. To celebrate (and in light of Labor’s superannuation back down last week), here’s an excerpt from Chapter 9 of Better Things Are Possible — “The Suddenwealth of Australia” — in which I chat to Thomas Walker, CEO of Think Forward, about how superannuation, tax, and generational wealth have shaped modern Australia — and how younger generations are right to question whether the system still works for us.

If you’re in Naarm/Melbourne, RSVP here. Excerpt below.

Is it a bird? Is it a plane?

No it’s superannuation. Today, for many younger working Australians, superannuation is one of those things that just is. Something few of us have put much thought into beyond, Yeah, it’s for our retirement, makes sense, and even fewer of us have looked into enough to know what kinds of companies our providers are actually investing in.

Tom explained that the current system lacks transparency, has a questionable track record on ethical investing, and could very well fail to deliver as promised for future retirees—Millennial and Gen Z retirees, that is. Having done some reading on the subject in preparation for our chat, the tiny pessimist within me forced me to admit to Tom that I feel like the system is failing, not just that it might. Tom said he was ‘suss on super as well’.

He highlighted the lack of control members have over their capital, noting that a lot of super funds channel money into global capital markets rather than reinvesting it locally. Instead of supporting the ‘real economy’—local businesses, jobs and infrastructure—these funds are often directed into financial markets overseas, prioritising profit over tangible economic benefits for Australians.

‘That fiduciary responsibility, to maximise returns for account-holders,’ Tom explained, ‘stops money from being invested in community projects that might not have such strong financial returns, but could have amazing environmental and social benefits.’ It probably shouldn’t come as a surprise that super funds would chase the highest returns, given their obligations. However, the fact that this approach leads them to avoid investing in projects with significant social benefits seems to contradict the very essence of the superannuation system—one that was designed with social benefit in mind.

Compulsory superannuation also reduces spending in the real economy. The 12 per cent contribution is money that could otherwise increase a worker’s taxable income and flow into local goods and services. Conversely, the age pension tends to stimulate the economy by transferring money to those more likely to spend it locally—on food, energy and essentials that create jobs and growth.

An Unfair Burden

It’s not just the real economy that suffers because of our superannuation system. Tom expressed concern about how the system unfairly benefits the wealthy. The basic structure seems simple: when your employer puts money into your super, you pay 15 per cent tax on these contributions. Then, once you’re over 60, you can withdraw that money tax-free in retirement.

This might sound fair, but it creates a huge advantage for high-income earners who would normally pay a much higher tax rate on their regular income than a low-income earner. These same high-income earners can also use super strategically to pay much less tax by building up their retirement savings through extra voluntary contributions at times in their lives when they don’t need the cash.

Tom envisions a progressive taxation system for both tax and super, requiring higher-income earners to contribute more in taxes, while offering reduced rates or additional support to those on lower incomes. For superannuation, this could mean adjusting contribution and earnings taxes to ensure a fairer distribution of wealth.

A critical aspect of Tom’s proposal addresses the misuse of the superannuation system as a tax shelter. He argues that while super was originally designed to reduce the tax burden on younger generations by reducing the funding needed for the age pension, its current use as a tax shelter for wealthier retirees has had the opposite effect, increasing the burden on younger people. Tom described to me how the lack of taxation on superannuation withdrawals allows retirees to ‘completely check out of contributing [financially] to society’ for decades.

The consequence?

Today’s 30-year-olds contribute twice the share of their total tax bill to supporting over-65s compared with what over-65s did back when they were 30. Why? Because super only covers individual retirement savings. It doesn’t fund the healthcare, age pensions or other public services that older Australians still rely on. With an ageing population, lower birth rates and longer life expectancies, there are now more older people around than ever and proportionally fewer working-age Australians to support them. The result is that younger generations are left to foot the ever-increasing bill.

In light of this, Tom’s proposal advocates for a tax system that is primarily wealth-based, rather than focused on age or income alone, to help rebalance the intergenerational tax imbalance and create a more equitable economic system for all Australians.

Even if his proposed reforms were accepted, though, Tom suggested to me that more fundamental changes may be needed. He offered two approaches: strengthening the age pension system to provide a more equitable foundation for retirement, and exploring the concept of community wealth-building. The latter approach would allow communities to control and direct investments from retirement funds into local businesses, ensuring that the benefits of those investments remain within the community to foster its economic stability and growth.

Looking to the future, Tom stressed the importance of participatory policymaking: ‘I think younger generations have incredible values around the community and the environment, and they really want to create a better future for Australia.

‘Millennials and Gen Z will be a powerful group that politicians can either work with, or ignore at their peril,’ he continued. ‘We want to build an economic system that we can be proud of. We do this by working across all generations and from different perspectives.’

I agree, Tom — if only there were an event in Brunswick on November 5 where we could put that into practice.

RSVP here. Grab a copy of Better Things Are Possible here. And if you’ve already read it, or some of it. Please leave a review or rating on your book retailer or choice/goodreads, it really, really helps 🫶🏼